Fictional cities … invite us to explore extraordinary urban landscapes that either defy the constraints of reality or let us better examine them.

The city can be an imagination. In most science fiction films, a city is transformed to resemble a space with radically changed structures, citizenry and functionalities (Sobchak, 1988). Framed within the subtext of fears, trauma, and temporal and spatial uncertainties, the fictionalised cities can project the desires, fetishes and angst of a given population.

How is a fictional city mapped? Is this a city of geo-referenced verisimilitude or a projection of what ought to be in the present. Alina Cojocaru opines that mapping a fictional city is “a fusion of past and present findings, a palimpsest of empirical observations and conceptual conclusions in order to bring new insights” (2018, 55).

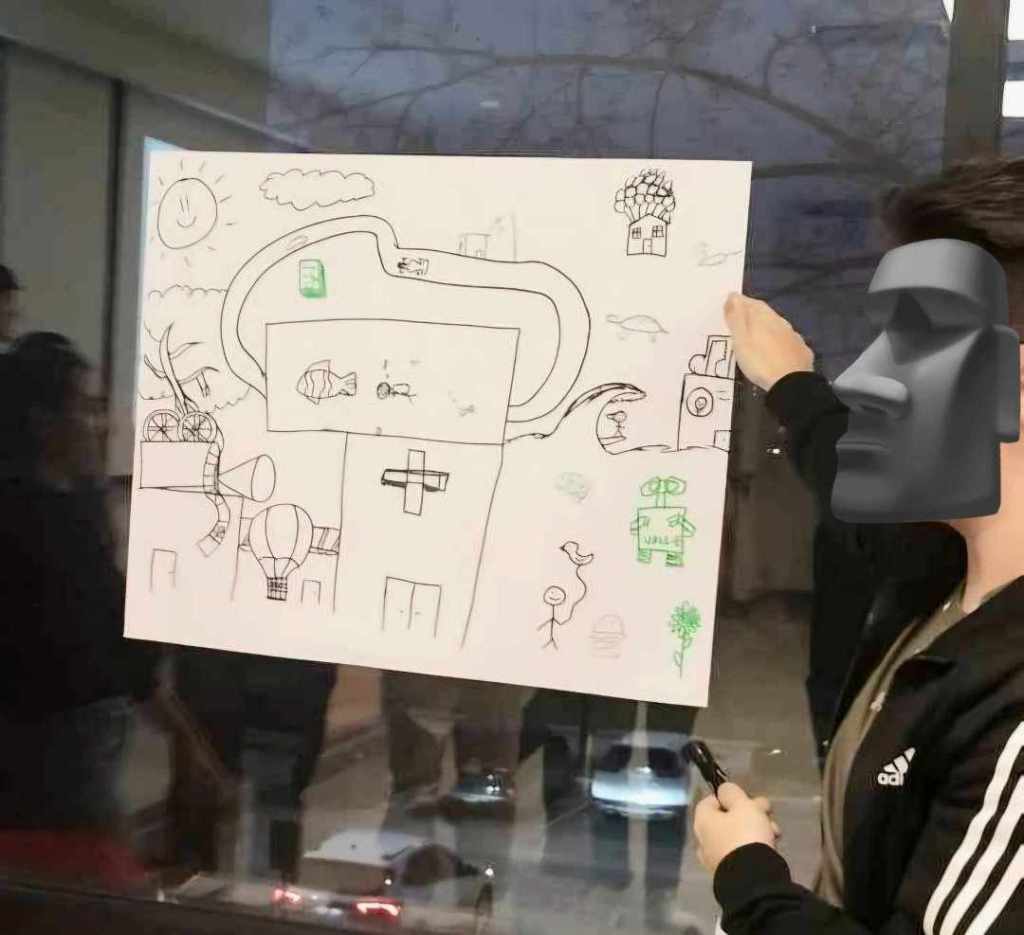

A classroom can be a fictional hinterland to encourage students to co-create fictional cities using their milieu as starting point. Mapping fictional city brings lived-in observations with imagination.

Students in the Urban Social Analysis (EU/Geog 3380) class at York University were asked to imagine and construct possible (alternative) futures of their city (Toronto), using their neighborhoods as prototypes. In the geonarrative mapping workshop conducted in December 2024, students were to draw and animate a section (singly and in tandem) of their neighborhoods and imagine that space as representing a small fragment of a fictional city where amenities and infrastructures should be present to accommodate the needs of a given population.

The maps the students produced allude to what Doreen Massey calls the “imagination of the spatial and the imagination of the political” which spotlights multiple webs of relations between city denizens (students, residents) and the institutions of power (urban planners of Toronto), and how specific public needs are addressed.

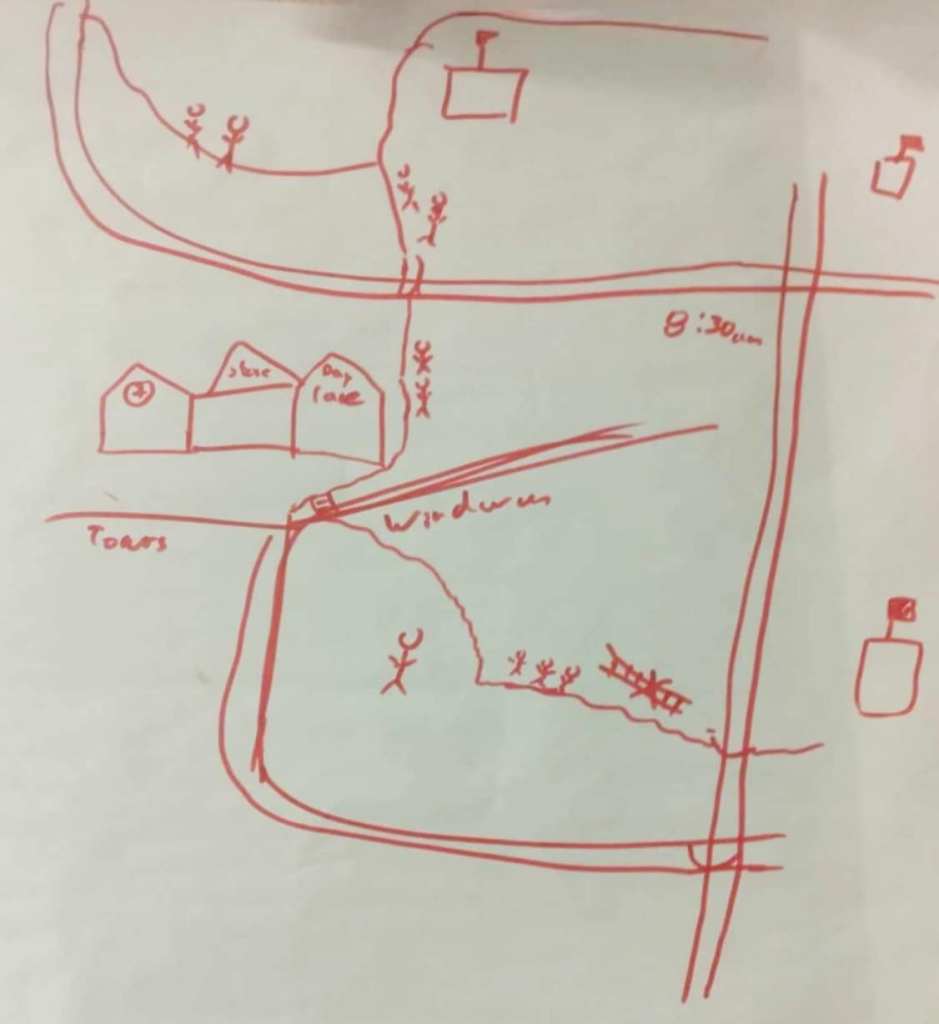

Map 1: Fictional Toronto neighborhood, EUC-York

The first drawn map shows the urban design of residential homes and the spaces of recreation catered to children and young adults. But the vast spaces are strangely not frequented (if at all) by children and most residential units appear closed off as though by design. The map’s large swath of empty spaces are likewise devoid of humans except near schools and day care centers. The lone stick figure is the creator of the map who observes the strangeness of empty spaces with no sign of frolic or play from children. The space is not for children. Drawn children are the imagined citizens of these empty spaces.

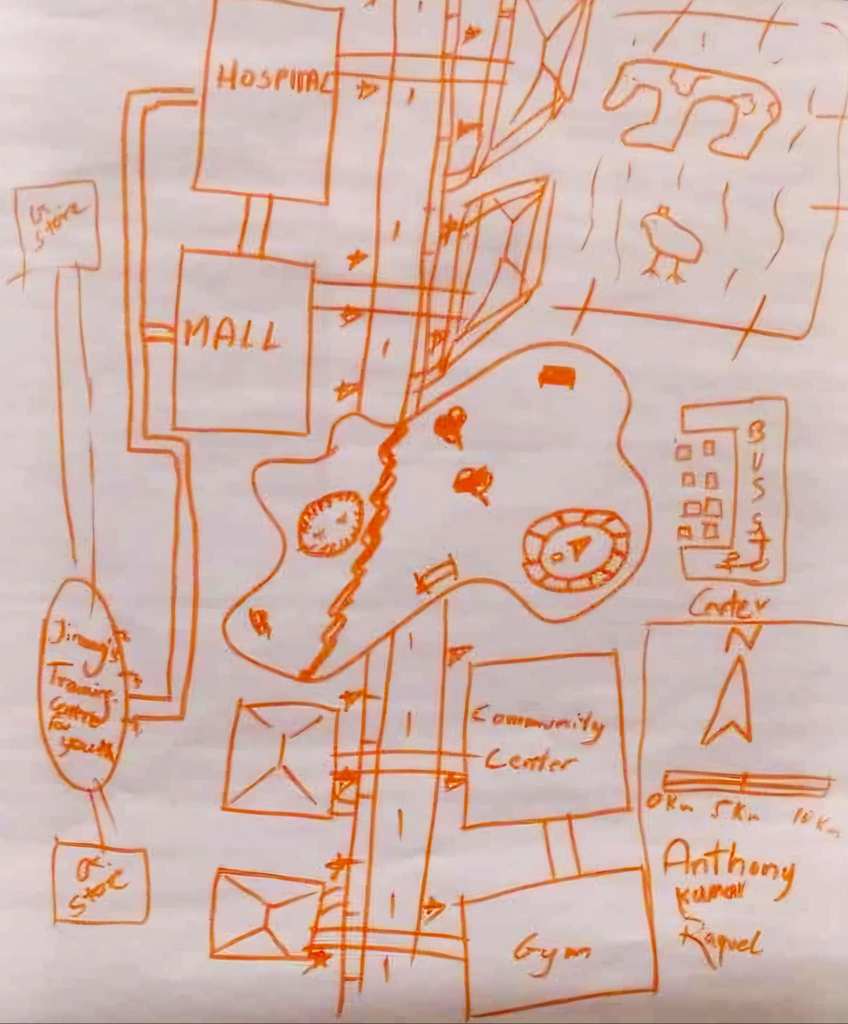

Map 2: Fictional city, EUC-York

The second map imagines a city neighborhood where proximity of infrastructures that links gym, community center, mall, hospital and school gives a portrait of a space that are entangled with each other. The zoo occupies a prominent space in the tableau to cater to the mostly-children crowd. Centrality and accessibility are given importance in the map. The map creators claim that this fictional city brings together the elements that make for healthier co-existence even if none of the students who co-created the map mentioned that this is a representation of the actual communities they live in. The drawn map is a projection of what ought to be present to ensure that such an enclave remains vibrant and entangled with each other.

Maps are fantasies that visualise imaginaries combining lived experiences and idealised hopes for the future: a dialogue between the factual and the fictional city.

Joseph Palis

Acknowledgments

Students of Urban Social Analysis (EU/Geog 3380) class at York University, Environment and Urban Change (EUC) Faculty Ranu Basu and Philip Kelly, and graduate student/teaching associate Fatma Ugur.

References

Alina Cojocaro (2018). Building a Corpus: The Journey of Mapping the Body of a Fictional City, International Journal of Cross-Cultural Studies and

Environmental Communication, 7(1), pp. 55-59.

Doreen Massey (2005). For Space, London: Sage.

Vivian Sobchack (1988). Cities on the Edge of Time: The Urban Science Fiction Film, East-West Film Journal, 3(1), pp. 4-19.

Leave a comment