What scents shape the city? How does scent contribute to placemaking? How do we design smell environments in the city?

Victoria Henshaw, 2013

In Nikolai Gogol’s satirical short story The Nose (1836), Collegiate Assessor Kovalev’s nose went missing. “The nose can’t have removed itself

of sheer idiocy,” Kovalev thought. The nose turned out to have gained agency, had a life of its own, and proceeded to outrank Kovalev in terms of status and prominence.

The nose in The Nose is a satire on the fetish of ordinary Russian people on ranks and upward mobilities in the wake of Peter the Great’s establishment of ranks based on upstandingness in society, regardless of nobility status. Apparently in The Nose, the nose knows.

Scents, smells and the nasal stimuli can also assist in other ways, such as one’s understanding of place. Smellscape was first introduced by J Douglas Porteous in 1985 as a way to tap the olfactory aspect to produce ‘smell maps’ and ‘smell marks’ and to acknowledge and enhance human experience of places. Kate McLean expanded the mapping of places through smell: “[I]ndications of geolocated smell possibilities and ephemeral scents combine visualization with the olfactory to place the emphasis on human interaction with sensory data to create meaning and an understanding of place” (2017, p. 92).

The widespread practice of cartography likewise embraced sensorial mapping that combines the experiential with the technical and creative aspects of map-making. In two examples of smellscape maps, both are geolocated in Philippine urban settings. It is important to note that these maps were a result of human experience of place at one point in time. These are olfactory snapshots of places that were mapped to provide us a glimpse of the layers of perceptions — perceptions of the mappers themselves. These are also indicative of the subjectivity of the cartographer as the map produced can provide insights to the particular and liminal spaces occupied by the mappers. The emotional dimension is also influential in determining that place’s specific smells and how these highly subjective perception of place will then be committed to the visual form that we call a map.

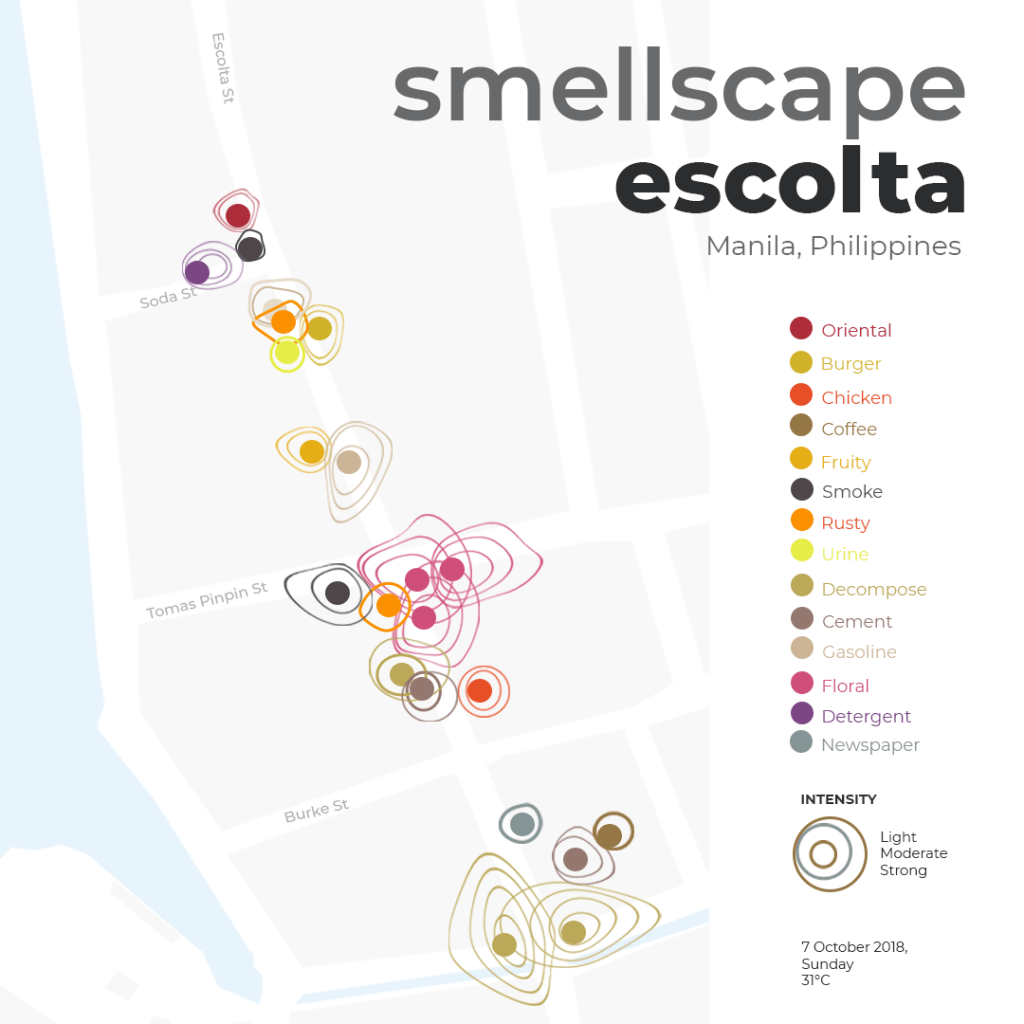

Map 1: Smellscape Escolta, B Mariano, 2018

Escolta, dubbed as the ‘Queen of Streets’, is a historically and culturally significant street located in the downtown of Binondo in Manila. It is known for its old structures and buildings which served as a commercial center since the Spanish colonial period. How can the olfactory sense contribute to placemaking? One Sunday in October 2018, cartographer Bryan Mariano conducted a smellscape mapping of Escolta – an adaptation of Kate McLean’s mapping projects of cities. The smells identified in Escolta are tightly linked not just to spatiality, but also to temporality. The spatial component of smells coincides with distance, location, and other multiple factors in the environment, and its temporality also depends on mobilities, air direction, among others. Rather than conclude that the smells indicated in the map remain the same throughout is to be reductive of places as homogeneous all the time. Bryan Mariano captured portions of observable and ethnographic experiences during that moment.

The smells identified and mapped out are symbolic-resonating issues such as gentrification (the floral scent was due to flower stands outside a newly opened furniture shop), and waste management (decomposition odor was due to the polluted canal and improper disposal of waste). Smells are also correlated to daily actions. In the corner of Escolta and Soda streets, the smell of pancit canton came from the exhaust fan, a guy smoking nearby and a woman washing clothes. The entanglement of those smells, food, smoke, and detergent, molecule by molecule, were all experienced by the mapper. There are smells which can be constant, like the controlled environment inside buildings and stores. There are also smells that are changing but kept on recurring: fragmented, and highly variable.

Escolta street on a particular weekend creates a spectrum of smells: it is a character of the place that is also constantly changing based on the cartographer’s emotional and psychological predilections. And you think a map is neutral and objective? Think again.

Map 2: Smellscape Map, RB Borje, S Suringa, M de los Santos; 2019

A map can also be interactive and can show not only the specific smells encountered by cartographers; three in the case of Map 2 — Michelle de los Santos, Arbi Borje and Sedric Suringa — as they navigate home-school traversals. Their olfactory experiences of places were color coded in the three maps that also portrayed their movements. Recording the spatio-temporal mobilities through time-lapse showed the distance traveled from the University to their home places. These maps managed to put an olfactory character to the rapid moving images that blur the streetscape into a fleeting tableau of people, vehicles, multiple activities, and infrastructures. This geospatial storytelling entangle smellscape with a plethora of urban characters: human and more-than-human.

In the map, space is lived experience – a quotidian engagement with site and situation, humans and non-humans, tension and order, among others. The smellscape map provides a sensorial layer that subjectively brings the audience to the personal perspectives of the three mappers and the places they engage in on a daily basis: living in Tandang Sora, Cavite, and in a dormitory on campus.

Both maps by Bryan Mariano and the tandem of Suringa-Borje-delos Santos creatively tell various geonarratives: of their encounters and engagements with space and place, and the use of the olfactory sense in creating smell maps that are particular and intensely personal. Like any other map, these smellscape maps are geohistorical snapshots of places — mindful of the ephemeral nature of ‘story maps’ and the particular time and space where the qualities of place were captured and depicted visually and, in the case of Lansa(ng)an map, in perpetual motion.

Joseph Palis

Acknowledgments

Sedric Suringa, Michelle de los Santos, Arbi Borje, and Bryan Mariano

References

Raquel Borje, Michelle de los Santos & Sedric Suringa (2019). LANSA(ng)an: Of Homes and Smellscapes, unpublished project for the graduate class in Cultures of Mapping and Countercartographies (Geography 292/293), Second Semester, 2018-2019, under J Palis.

Nikolai Gogol (1863/2015). The Nose, Penguin Classics.

Victoria Henshaw (2013). Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments (1st edition). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203072776

Bryan Joel Mariano (2018). Smellscape Mapping of Escolta, Manila, unpublished paper for the graduate class in Geohumanities (Geography 214/246), First Semester 2018-2019, under J Palis.

Kate McLean (2017). Smellmap: Amsterdam—Olfactory Art and Smell Visualization, Leonardo, 50(1): 92–93.doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_01225

J Douglas Porteous (1985). Smellscape. Progress in Human Geography, 9(3): 356-378 doi:10.1177/030913338500900303

Leave a comment