[W]here this world means potentially a hillside of shallow graves sticky with mud, blood, brain, guts, spades, cartridges and unutterable inhuman horror. Stripped down; hollowed out, winnowed away; splintered, shattered, smashed; dis-assembled, dis-located, dis-membered; subtracted from, again, again, again: such is the melancholy cry, or embittered scream, of a less-than-human geography.

Chris Philo, 2017, p. 258

We experience violence all our lives according to geographer Marcus Doel in his book Geographies of Violence … ‘[violence] has been industrialized and domesticated’ (4, 2017). Chris Philo offers the notion of less-than-human geographies that take away the human in the tableau of the living. In his discussion of terrorism with violence, Terry Eagleton ponders that “more violence … breeds terror which in turn puts blameless lives at risk” (2010, 159).

While geographers have written extensively on multiple forms of violence: physical, structural, ecological, epistemic, also genocide, ‘terrorisms’ (from domestic to global) and geotrauma (Pain 2020) among others, what remains one of the challenges is in the visualisation and in the representation in graphic form of these various forms of violence. How to cartographically portray something that eludes easy capture and one that is fraught with various cultural understandings. What palimpsestic stories can be excavated from the visual articulations found in these cartographic images?

Below are stories of three maps that engender the magnitude of violence from various scales. Data that served as basis for these images came from available news sources, from products of painstaking research, and from reconceptualisations of big data to present harrowing pictures of violence in multiple spatio-temporalities.

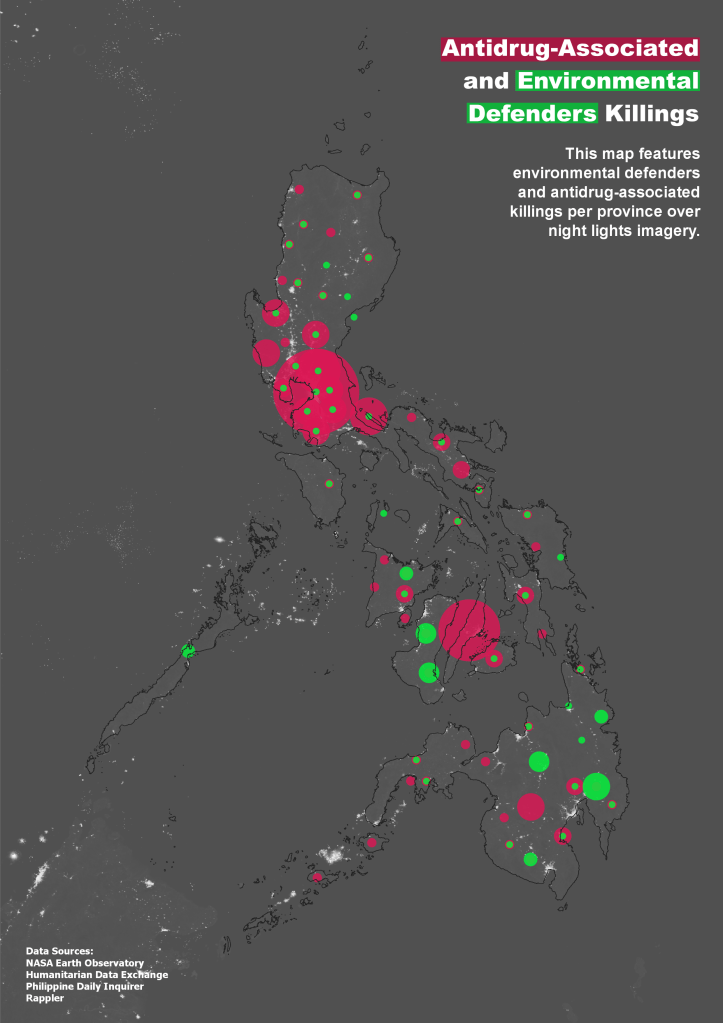

Map 1: Antidrug-Associated and Environmental Defenders Killings, AJ Adovo, 2021.

Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs resulted in the dramatic rise in drug-related extrajudicial killings. In the report by Jeroen Adam, Joel Ariate and Elinor May Cruz (2019, 1), it claims that:

Violence, and the explicit call for violence as a means to achieve political ends, were key features of Rodrigo Duterte’s campaign for the presidency in 2016.

Arvin Jake Adovo’s map shows the blots of violence when projected on the Philippine archipelago. Map 1 above which saw life as an undergraduate requirement submission in a Mapping and Countercartographies class, was based on available data provided from online publications. Situating violence not as a Manichean concept but always grounded on the ‘specific, contingent, and contextual’, Adovo asserts that:

Deaths piled up as if mere numbers without a story. A corpse on the street became old news. As Duterte faces the International Criminal Court, these killings are not merely normalized—they are excused.

A graduate student in Geography at the University of Melbourne, Adovo’s initial interest in violence was first linked to the social construction of ‘dark’ although nightscape studies have since championed the ‘positive qualities of darkness’ as well (Edensor 2012). However Adovo makes clear that dark-light temporalities were not the inspiration for this map of violence.

I was particularly interested in mapping these violent landscapes reflecting on the ‘dark’ as an often-feared timespace—but violence happens even in broad daylight, in a crowd full of people. This might be the emblem of violence: it always runs over and disrespects. Violence cuts.

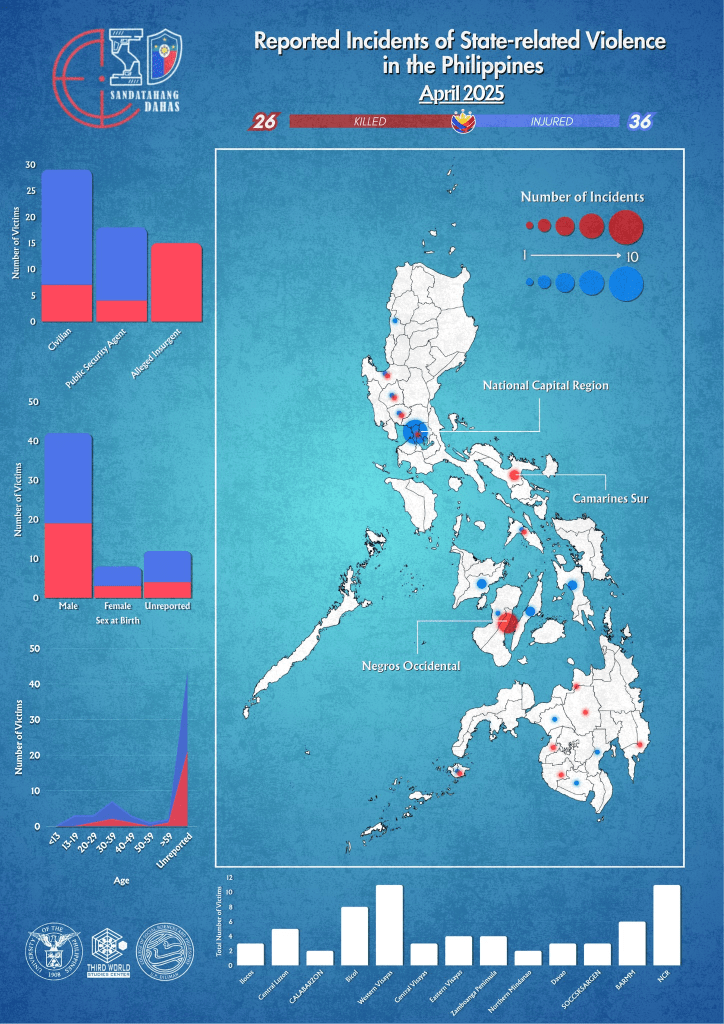

Map 2: Reported Incidents of State-Related Violence in the Philippines, TWSC 2025.

Dahas means violence in Filipino. The Dahas Project of the Third World Studies Center (TWSC) of the University of the Philippines-Diliman came from the Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy (VHRD) project in 2022 that TWSC co-created with Ghent University. The site documents the drug-related killings in the country. Sources were culled online from various reportage and social media posts.

Map 2 is the latest report of killings in the Philippines: the website lists 989 casualties as of 31 May 2025 under the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. Although the map above shows the cumulative number, stories that accompany each casualty are officially reported but background information remain hazy and generalised. In the document published by the Dahas Project website, it states that “no systematic reporting of deaths resulting from drug operations has been published by the Marcos Jr. administration” (2025, 2). Not all who were killed were suspected of drugs. Some are civilian informants while others are barangay officials who were targeted in “drug-related retaliatory attacks” (2025, 5).

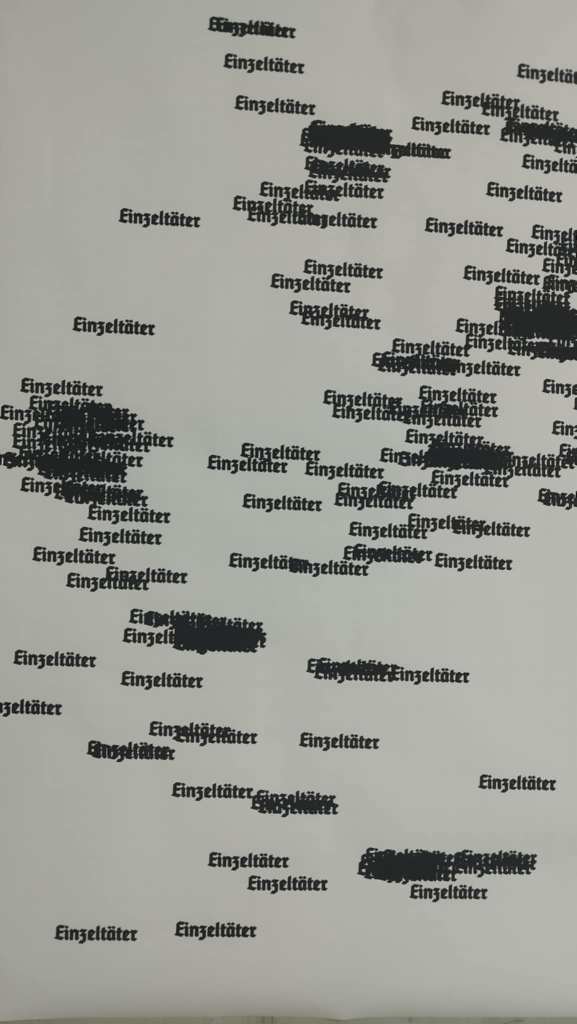

Map 3: Einzeltäter, E K Schick, 2025

After the right-wing terrorist attack on a synagogue in Halle (Germany) in 2019, in which the perpetrator shot two people after unsuccessfully trying to enter the synagogue, there was a lot of talk in the media about the so-called ‘lone perpetrator’ or ‘lone wolf shooter’ theory. Germany has a tradition of not acknowledging right-wing terror attacks as politically-motivated. It was only after a shooting in Munich in 2016, where officials actually only acknowledged the attack as right-wing terrorism a few weeks after the attack in Halle — over 3 years after the attack happened. Shooters tend to get called mentally ill and are believed to have acted entirely alone.

As a communication design student at Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle, Elia Schick’s poster (Map 3) was a product of research of all the deadly right-wing attacks in Germany since 1990 (according to the Amadeu Antonio Stiftung). The word “Einzeltäter” was placed on the locations of the attack on the map. After removing reference points in the map, there was this overall image of the so-called lone wolf shooters that form the shape of Germany. Elia thinks the image of a lone wolf shooter — an Einzeltäter — dangerously ignores the right-wing networks in Germany (as well as worldwide) which spread through the internet and where people connect with each other to spread hatred and radicalize each other. Elia writes:

Right-wing attackers don’t work on their own, they grow in an environment of uprising right-wing ideas and languages in our political landscape and are well connected with like-minded people around the globe … At the time I was just really angry of the media and the political landscape covering the attack in Halle and wanted to comment on the “Einzeltäter-Theory” to make a political statement against these narratives that trivialize right-wing terrorism in Germany.

Much like any art, text or statement, a map can communicate to a wider audience and can be interpreted in a myriad of ways. After Elia distributed his map in public places and online, he received various feedbacks. He recalls:

I posted it online in the beginning of 2020 after another right-wing terrorist attack in Germany and it gained a lot of support and lots of people shared it. I then decided to make it available for free to download in different sizes and lots of people and groups printed it out and put it in public spaces mostly the big cities. Over the past years I occasionally get approached by different people and institutions who wanted to use it in a publication or exhibition and I tried to always update the map whenever it is used somewhere … I got a lot of positive feedback but there were also some negative reactions out of the right-wing field especially online. Someone even made an angry youtube video about it and I’ve seen some posters got ripped off walls.

Elia credits his training at the ‘Studiengruppe Informations design’ at Burg where design practice is based on an individual’s political belief systems, by taking a stance and being partisan.

All the maps show examples of less-than-human geographies that Chris Philo mentioned — an approach that “diminishes the human, cribs and confines it, curtails or destroys its capacities, silencing its affective grip, banishing its involvements: not what renders it lively, but what cuts away at that life, to the point of, including and maybe beyond death” (258).

But perhaps, what is ultimately tragic about the reportage of killings as shown in three maps, is human complicity to these forms of violence. As Eagleton reminded us in the conclusion of On Evil: “More violence … breeds more terror, which in turn puts more blameless lives at risk. The result of defining terrorism as evil is to exacerbate the problem; and to make the problem worse is to be complicit, however unwittingly, in the very barbarism you condemn.”

Joseph Palis, with Elia Kim Schick and Arvin Jake Adovo

—–

Acknowledgments

Arvin Jake Adovo, Elia Kim Schick, Joel Ariate, and the University of the Philippines Third World Studies Center (TWSC).

References

Jeroen Adam, Joel F Ariate and Elinor May K Cruz (2019). Violence, Human Rights, and Democracyin the Philippines, Kasarinlan, 34(1-2), 1-14.

Marcus Doel (2017). Geographies of Violence, London: Sage.

Terry Eagleton (2010). On Evil, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tim Edensor (2012). The gloomy city: Rethinking the relationship between light and dark, Urban Studies, 52(3) 422–438.

Rachel Pain (2020). Geotrauma: Violence, place and repossession, Progress in Human Geography, 45(5), 972-989.

Chris Philo (2017). Less-than-human geographies, Political Geography, 60, 256-258. Less-than-human geographies

Third World Studies Center (2025). Drug-Related Killings in the Marcos Administration, Year 2 (July 1, 2023-June 30, 2024).

Leave a comment